mer·i·toc·ra·cy /ˌmerəˈtäkrəsē/ noun government or the holding of power by people selected on the basis of their ability.

What makes for a good life? What makes you successful? A steady income; a fulfilling career; a loving family? What is success anyway? I’ve been pondering over these questions for some time now.

The plethora of human experience that explores and experiments with the idea of success has found expression in various art forms throughout history. From the records of the triumphs of Gilgamesh to the corny articles on Medium (even as the latter accumulates copious amounts of both applause and vitriol every day,) success has been an idea we humans obsess over.

In the very early days of the social primate, and of our ancestors before them, success simply would have equated survival. It’s formula: eat well, rest enough, procreate and don’t become a predator’s meal; repeat for as long as biologically possible. Responding to stimuli was a remarkably simple process too: Fight, or Flight. If you decided wisely, you survived. The ones with less fortune perished, and the world moved on.

We still make hundreds of fight or flight decisions every day, but the stimuli have changed dramatically that the simple, binary system of decision making might not work as effectively when faced with them. Our adversaries come in the form of large, frightening predators no longer. Rather, we must now respond to the dynamics of technology, the economy and the arguably Kafkaesque society itself.

Mere survival then becomes a trivial pursuit. True success now demands an ultra-noble, larger-than-life, often bloated sense of urgency to achieve a grandiose state of existence that measures beyond a dull, ordinary life.

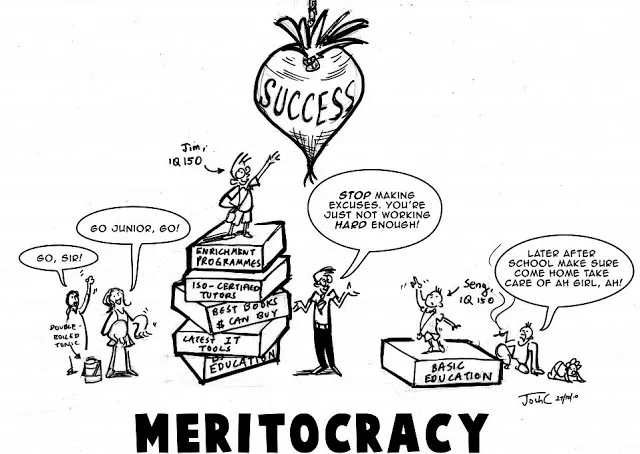

Yet, true to our evolutionary roots, we still have in place (more so in the West than in countries like Sri Lanka) a perfect economic system that ensures the survival of the fittest: a meritocracy.

On the surface, a meritocracy sounds like a wonderful idea, a utopian dream. The truly able and accomplished will take the helm of society, in turn motivating the subsequent layers to achieve more and rise up. It’s a system that offers opportunities to the ones worthy of them, and praises where praise is due. In fact, this is the very system that idealistic, potentially-world-changing, Valley-style companies (mostly operating in economic sectors that have gained popularity thanks to Western Capitalism) embrace in the hope of faster growth, better products and services, and happier employees. It makes people work harder and set more ambitious goals, and it rewards people when they work harder and achieve ambitious goals.

What could possibly go wrong?

In an extreme meritocracy, what happens to the people who, in the eyes of society, lack ambition, the ones who fail to achieve an arbitrary level of success?

Take an average blue collar worker who earns minimum wage. He works for an unseen boss and continues to do so even with the knowledge that a machine will replace him soon, has no savings account, is in constant debt, is uneducated and pays no heed to the goings on of the larger world beyond his little island. In a meritocracy, he’s a loser. He’s someone not worth paying any attention to.

Until he rallies up his buddies and votes elitism out.

If America’s rust belt comes to mind, yes, that is indeed what I am referring to. If that seems like a far-flung reality that is difficult to relate to, wait and see what happens to the current government in Sri Lanka in a couple of years.

A meritocracy invariably gives rise to an elite class. The educated, globalist, over-achieving Lib Dems who, often with no evil intentions, treat the lower end of the gene pool with disdain. That education determines value is a misconception, and countless examples throughout human history tells us just that. But even to this day education is one of the surefire ways of upward social mobility. The ones going up loose touch with ones in the bottom. What’s intriguing to me is that failure — a concept romanticized by the Silicon Valley elite and spread like wildfire in the contemporary business world, and in the modern society by extension — is a reason for pride for the privileged and an inglorious misfortune for the rest.

Even those who have not lost out yet in terms of economic power are fearful that they might. The causes of inequality, particularly advances in information technology, are not going away soon. These perceptions have damaged people’s sense of economic security, even beyond what economic data reveal to be objectively true.

– Nobel Laureate Professor Robert Schiller

Falling economic performance and rising inequality (in the eyes of those underprivileged, because it’s not getting any better for them) results in economic nationalism. To the average citizen, a dozen charts showing how things are getting better is devoid of any meaning. The only thing she’d care about is her own personal reality. A better-off neighbor is reason enough to believe that she is being mistreated by the society in some way.

Enter Trump & Co. This populist wave is now an easy one to ride. We know what happens next.

What all this leads to is an inevitable decline of the health of societies. (This idea of health is not a straightforward metric. But because economics itself is not a hard science, a make-do definition will suffice for now. Best defined, this societal health is measured in terms of level of trust, life expectancy, level of education, mental illness and a number of other criteria.)

What then is the role of governments? Am I trying to make a case for more social welfare, or more intervention to ensure fairer wealth distribution? Wouldn’t such societies be breeding ground for complacent and unambitious people?

The answers to these questions don’t come in black and white. The stratified society is a strange animal to deal with. It could very well be inclined to bite you, yet perfectly be happy with me petting it. This is why there is are perfect models or replicable templates for national economies. This is why, as acclaimed economists like Angus Deaton will be quick to point out, we cannot throw away our existing models and build a flawless economy from scratch. The beast feeds on whatever its immediate environment provides it with. It might just wither and die when uprooted.

Therefore, while I certainly can’t claim to have any answers, I’d be content to open your eyes to the questions we all must face.

Leave a Reply